Oldies but Goodies

Un-Banned Because Book-Banners Haven’t Heard of Them

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911) gets called racist and colonialist largely because it’s well-known; I reject these accusations. A host of others, not as prominent but still disappeared from school libraries, remain wonderful reads. Two of these, E. Nesbit’s The Phoenix and the Carpet (1904) and Elinor Farjeon’s The Glass Slipper (1955) are not to miss. Read them aloud to your seven-to-ten year-old; naturally, some younger and many older children will enjoy these lyrical tales as well. At the same time, it’s fun to titter over the silly reasons these books might be censored today.

Looking over these older books—The Phoenix and the Carpet first appeared in 1904 and The Glass Slipper in 1955—I’m struck by the richness of the language. Lovely descriptive phrases, eccentric names, and rhymes are far less common in contemporary children’s books. Near the beginning of Nesbit’s tale, some children get ahold of firecrackers and set them off indoors. “The flame was spreading out under the ceiling like the rose of fire in Mr. Rider Haggard’s exciting story,” Nesbit writes. The rose of fire! Where would you get a simile like the rose of fire in contemporary children’s writing? I haven’t found one.

The firecracker event is enough to freak out parents and teachers today—God forbid children get ahold of firecrackers! Why would you give them the idea of setting them off anywhere!

But any parent can explain to a kid we don’t set off firecrackers, especially not indoors—besides, in the story, the consequences are unpleasant enough to deter all but the psychotic.

The real disadvantage for the modern parent is not the dangerous activity, but the need to explain a thing or two: “Oh, Rider Haggard’s a thrilling writer I can read you sometime! And when those British kids say something is ripping they just mean it’s cool.” So you’ll have to look up a little vocabulary. Big deal.

Though I love Judy Blume—she’s a terrific storyteller with a great grasp of the inner torments of children—she’s less lyrical. Straightforward, hilarious, hitting-the-nail-on-the-head, yes. Lyricism does seem to be going out of style. These older books originated in a world in which people took more time with language, had the leisure to observe. Long descriptive scene-settings were expected, welcomed, when the visual mainly appeared through words, not a series of instant images. Children read more and parents or teachers or governesses read to them. Dialects tended to be poetic—they still do. How well I remember my North Carolina father advising me that you “cain’t make a silk purse outen a sow’s ear.” Derived from the earlier Scots version. Writing for children in general was more poetic. Oh, the world before cell phones or regular old telephones—neither were common in many English homes before the nineteen-thirties. No TV, and naturally, no vile TikTok.

In Farjeon’s retelling of the Cinderella tale, as poor Ella must rouse herself from her chilly pallet at the crack of dawn, we get amusing doggerel, including:

Bing-Bong!

Bing-Bong!

It’s exceedingly wrong

To stay in bed long.

All the things in the kitchen yammer in rhyme, giving us a strong sense of the demands made by the mean stepmother and stepsisters, Araminta and Arethusa:

Light me!

Oil me!

Sweet me!

Boil me!

Mend me!

Make me!

Clean me!

Bake me!

Poor mistreated Cinderella rises to the occasion, tidying up the kitchen in her very cold bare feet and readying breakfast for her deadbeat dad, who’s terrified of his wife and who doesn’t defend his daughter, and for her nasty stepsisters. The wicked stepmother never has a name but she’s plenty wicked—what we’d now call abusive: she steals a miniature portrait of Cinderella’s mother from under Cinderella’s pillow and threatens to smash it unless Cinderella rips up her invitation to the ball. She calls Cinderella “slut” too—but by the end, her stepdaughter stands up to her and says, “Father doesn’t love you!” The stepmother tries to hit her over the head with the broom, but the broom has a mind of its own and smacks the stepmother in the face.

Tsk, tsk, violence, the modern mom will say. But she would be wiser to croon, “this is just a story.” In a story, you can do anything you like, including things we would never do in real life. That’s the point.

Naturally the Fairy, disguised as an old woman, appears to restore Cinderella’s invitation, provide the dress and the coach and the usual accoutrements, and naturally Cinderella gets her prince. I can imagine the objections today: she’s portrayed as a poor, starved abused drudge whose only ambition is to be the good wife of a prince.

A host of stereotype-bashers have risen up around the original Cinderella tale; there’s one set in the wild west, there’s the amusing, silly Prince Cinders, about a boy who has to clean up after his mean, bigger brothers, there are Cinderellas of every nationality and ethnicity and at least one trans Cinderella .

In Farjeon’s version, there’s some hint that happily ever after isn’t endless paradise—the prince and Cinderella have “left a part of themselves in Nowhere, where wishes come true.” She’s been known as a princess from Nowhere, perhaps as a nod to the unreality of constant happiness. But it’s clear these two will get along just fine.

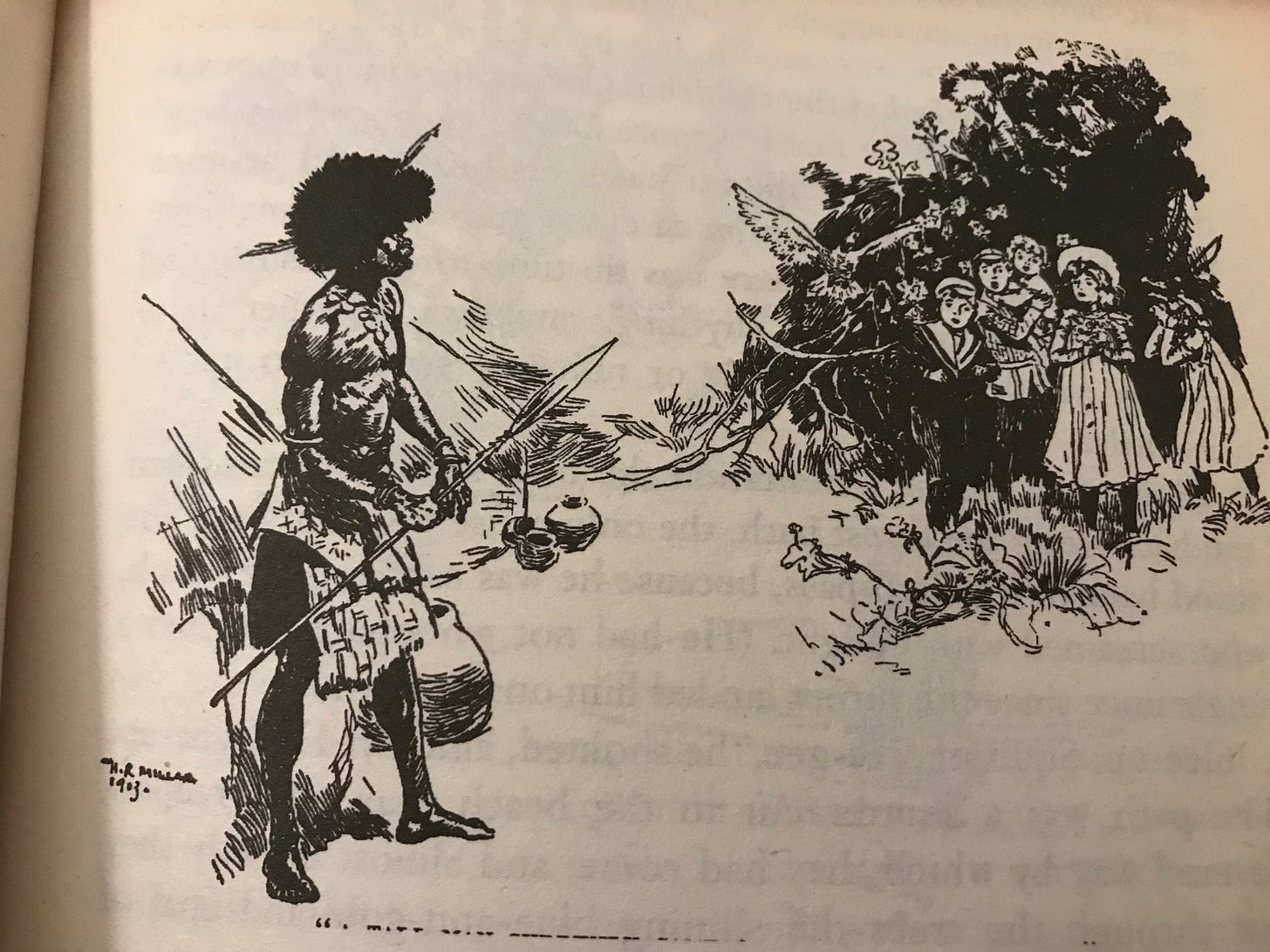

Nesbit’s The Phoenix and the Carpet is the second in a trilogy of novels involving magic. In the first and best known, Five Children and It, (1902) a snail-like sand creature known as the Psammead grants wishes that go comically wrong. I felt like the kids didn’t have enough fun, but they do in The Phoenix and the Carpet, in which many wishes bring delightful adventures. The bird itself is a bit of a pill; it thinks, for example, that the Phoenix Insurance Fire Company is a temple devoted to him, and demands worship. A few scenes would be designated “racist” and “colonialist” today. In one, worried about their sick baby brother, “the Lamb,” the older brothers and sisters wish “we were on a sunny southern shore, where there can’t be any whooping cough.” Lo! They find themselves and their cook on a tropical beach with “golden smooth sand,” but also “savages.” A tall man appears, who had “hardly any clothes, and his body all over was a dark and beautiful coppery colour.” He’s holding a spear.

He and his fellow tribesman begin dancing around the cook, who seems to think she’s dreaming and pays them no mind. The children get worried: are these folks cannibals? Or as Wikipedia piously puts it: “In Chapter 3 of this novel the children encounter people described as having copper-toned skin, whom they immediately assume are savage cannibals.” Not so fast, Wikipedia. What happens is this: having arrived on a tropical island, the kids assume it has inhabitants, that these inhabitants are “savages,” loosely defined as folks who wear few or no clothes. They wonder if the savages are cannibals.

And they aren’t, Wikipedia! These “savages” just want a cook. They dance around her with flowers until she agrees to live with them, become their queen and cook for them. Soon thereafter, another wish brings her a husband—a burglar who wants to be in a different line of work. He marries the cook and the two are set to live happily ever after. The baby is cured of his whooping cough (no small feat in the pre-antibiotic world) and the kids go on to their next adventure. For those clinging to the notion that dark-skinned persons are stereotyped as “savages” or “cannibals,” let me point out:

(1) Cannibals existed and still exist. In several shades of ethnic.

Nelson Rockefeller’s son was consumed by cannibals, as noted in my earlier post defending Babar. The notion that your child will see one dark-skinned person in a grass skirt and imagine that “savagery” and cannibalism are traits of dark-skinned persons is ludicrous.

(2) The dark-skinned savages in The Phoenix and the Carpet employ the white, Irish cook as their cook—making her queen and praising her and her husband. They serve and, indeed, worship her with flowers and dances so that she will continue to cook for them. Is that racism?

Before I close, one more lovely, neglected book came my way recently—Elizabeth Enright’s Gone-Away Lake (1957). A lovely tale of sympathy between generations—and one line sticks with me: Eleven-year-old Portia sits down to read “a very good book called Wuthering Heights.”

How many eleven-year-olds tackle Wuthering Heights now? Oh, if you did, write to me! I’d be thrilled to hear from you.