Empathy and Anti-Racism in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden

It’s No Secret: The Book's Already "Decolonized"

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1911 book, The Secret Garden—that masterpiece of childhood triumph over tragedy—is, contrary to popular belief, anti-racist.

Yes, even the scene in which nine-year-old Mary Lennox, ignored by her parents and dumped on the help, says Indians aren’t people, “but servants who must salaam to you.” Which should be understood not as racism but rather as the position in which she’s always found herself—that of a contemptible underling. Her father, Captain Lennox, is too busy with his post in the British army in India to bother with her. Her socialite mom cares only for parties. Admiring her mother’s face and dresses “full of lace” from afar, Mary doesn’t dare speak to her, and never mentions her father. When both parents die, she doesn’t grieve, having never known them.

The book subtly critiques Mary’s disdain for Indians from the get-go. Readers know it’s a point of view held by a naïve young child of whose upbringing the narrator thoroughly disapproves.

The Secret Garden opens with skinny, sallow, spoiled rotten Mary Lennox:

When Mary Lennox was sent to Misselthwaite Manor to live with her uncle everybody said she was the most disagreeable-looking child ever seen. It was true, too. She had a little thin face and a little thin body, thin light hair and a sour expression.

Her parents, we’re told, never wanted her and don’t want to hear her cries or be bothered by her presence. The ayah’s, or nursemaid’s, job is to keep the child quiet at all costs, so that by the time she was six years old she was as tyrannical and selfish a little pig as ever lived. Nobody likes Mary, and no governess will stay. Disliking everyone, she plays alone. Her life might have gone on that way if her entire family—and her ayah and ayah’s family—hadn’t been wiped out by cholera in a matter of days. The sole survivor, Mary is removed from India and sent off to Yorkshire to live with her mysterious uncle. Spirited and crabby, Mary is bored, but undaunted. The night she arrives, she’s startled by the moors, never having seen anything like them in India, and the next morning she is startled by the maid cleaning out the fireplace.

In the following scene—deemed racist by everyone, apparently, except me—Mary confronts Yorkshire-born Martha, who, unlike the Indian servants, fails to kowtow to her. The ensuing confrontation is one in which Mary and Martha begin to learn about their different worlds:

“What do you mean? I don’t understand your language,” said Mary.

“Eh! I forgot,” Martha said. “Mrs. Medlock told me I’d have to be careful or you wouldn’t know what I was sayin’. I mean can’t you put on your own clothes?”

“No,” answered Mary, quite indignantly. “I never did in my life. My Ayah dressed me, of course.”

“Well,” said Martha, evidently not in the least aware that she was impudent, “it’s time tha’ should learn. Tha’ cannot begin younger. It’ll do thee good to wait on thysen a bit. My mother always said she couldn’t see why grand people’s children didn’t turn out fair fools—what with nurses an’ bein’ washed an’ dressed an’ took out to walk as if they was puppies!”

“It is different in India,” said Mistress Mary disdainfully. She could scarcely stand this.

But Martha was not at all crushed.

“Eh! I can see it’s different,” she answered almost sympathetically. “I dare say it’s because there’s such a lot o’ blacks there instead o’ respectable white people. When I heard you was comin’ from India I thought you was a black too.”

Mary sat up in bed furious.

“What!” she said. “What! You thought I was a native. You—you daughter of a pig!”

Martha stared and looked hot.

“Who are you callin’ names?” she said. “You needn’t be so vexed. That’s not th’ way for a young lady to talk. I’ve nothin’ against th’ blacks. When you read about ’em in tracts they’re always very religious. You always read as a black’s a man an’ a brother. I’ve never seen a black an’ I was fair pleased to think I was goin’ to see one close. When I come in to light your fire this mornin’ I crep’ up to your bed an’ pulled th’ cover back careful to look at you. An’ there you was,” disappointedly, “no more black than me—for all you’re so yeller.”

Mary did not even try to control her rage and humiliation.

“You thought I was a native! You dared! You don’t know anything about natives! They are not people—they’re servants who must salaam to you. You know nothing about India. You know nothing about anything!”

Here’s what’s anti-racist: the narrator isn’t holding up this exchange as a model of human civilization. We’re not meant to approve of Mary’s notions of who is human and who isn’t. We’re meant to challenge her ideas about race. It’s in this scene that Mary begins to learn the meaning of words she’s only parroted up to this point. She has a tantrum, gets talked down from it, and begins to see people differently. It’s really her sense of self that’s been assaulted by Martha’s hope she’d be black. Mary’s been trained to see dark-skinned people as inferior, and it is Martha who talks her out of that.

Like many young children, Mary assumes everyone knows what she knows. I remember a three-year-old running up to me in a playground, asking, “Where’s Mommy?” Naturally, it didn’t occur to him that that I didn’t know what his mommy looked like. For Mary, her new environment is shockingly different. From her point of view, Martha knows nothing about the world.

We’re thrilled to see Martha putting Mary in her place, telling her she really ought to know how to dress herself by age nine. Plus, Pointing out that black men are “brothers.” Just the reverse of what Mary’s been taught. We’re also meant to enjoy Martha’s curiosity about Mary’s origins and about India.

Martha’s in fact “doing the work” as Robin DiAngelo would have it. In just the line the wokerati pounce upon, there’s a critique of racism. Namely: there’s such a lot o’ blacks there instead o’ respectable white people. When I heard you was comin’ from India I thought you was a black too. Trying to understand Mary’s rudeness, Martha assumes Mary behaves badly because she comes from a place where the people look different. That difference—their skin color—is initially linked in Martha’s limited experience. Spitfire Mary, indignant to have been insulted, is brought up short by levelheaded Martha, who makes up in common sense what she lacks in education: I’ve nothin’ against th’ blacks. When you read about ’em in tracts they’re always very religious. You always read as a black’s a man an’ a brother. I’ve never seen a black an’ I was fair pleased to think I was goin’ to see one close.

In other words, Martha enjoys a lively inquisitiveness about life beyond her surroundings. She’s eager to see a black person the way I’d be eager to see a Martian, especially if he had antenna protruding from his head, and spoke like Ray Walston. She’s never seen anyone who wasn’t white and from Yorkshire.

In 1985, I was staying at an Irish B&B. A young man from Kenya arrived; he was on his way to boarding school in the U.K. and his worried parents phoned the proprietor to make sure he’d arrived. Standing behind him as she spoke on the phone, she reassured the parents, serving the young man oatmeal at the family-style table where guests ate. How she stared! Her eyes got all round. She’d never left Dublin and I’m pretty sure she’d never seen a black person.

That’s Martha’s state of mind. Mary is quick to insist on her own point of view—the inferiority of “natives”—and Martha is equally quick to dissuade her and reprove her for her uncouth language. Mary bursts into tears, but before long she’s moved by Martha’s kindness to change her ways. She’s even code-switching by the end of the book: she so admires Martha, Martha’s brother Dickon and his love of animals, Martha’s mother, who sends her a jump rope and delicious snacks, that she does her best to speak broad Yorkshire dialect.

Alas, so many well-meaning parents deprive their children of this lovely story. One mother’s comment—a typical one—was: “I skipped that whole book, setting it on a shelf for later, noting that it would have to be accompanied by an appropriate conversation about colonialism and ugly views of native peoples.” No, no, no. And the other complaints— about Colin’s illness, don’t much hold up.

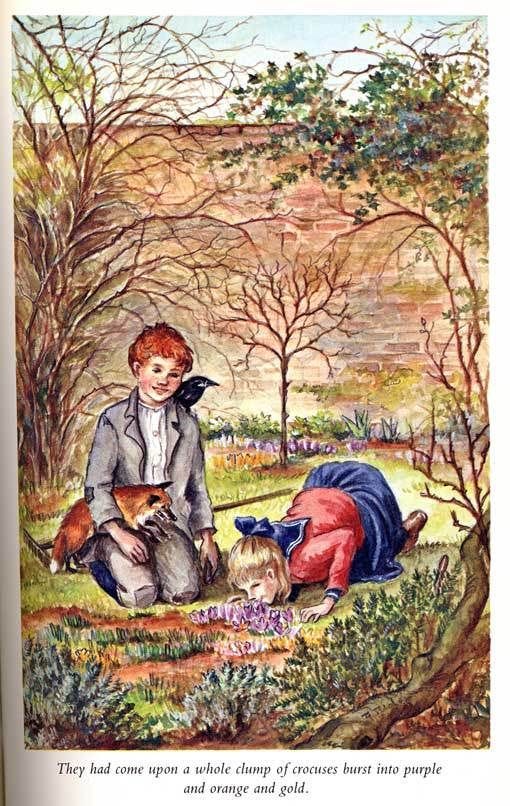

Colin, Mary’s secret cousin, is tucked away in the Yorkshire mansion where she’s not supposed to discover him. She hears someone crying and is told (even by Martha!) that it’s just the wind or the scullery maid. Never one to cave in, Mary explores the corridors until she finds the source of the howling, her cousin Colin, an invalid who can’t walk, whose mother died tragically at birth. Like Mary, he’s been brought up badly: encouraged to think he’s going to die, he’s given everything he wants, never goes outside, and spends most of his time throwing temper tantrums. These two cantankerous children end up healing each other—Mary, by interesting herself in another person’s needs and Colin by offering friendship as he finds the courage to exit his room, at first in a wheelchair, and go to the garden with Mary. In the fresh air, the children get well. The message that life renews itself as Winter (grief and death) moves to Spring (life and hope) is a lively and timely one.

But it’s just such stories educators deprive children of now. The idea that the characters must be of different races—a popular idea, to be sure—for the book to be “anti-racist” is a false one. As we’ve all seen, books billing themselves as anti-racist simply offer a new form of racism, announcing that white people invented racism. And (according to Megan Madison’s Our Skin and too many others) said they were “prettier” and better in every way and “deserved more.”

The point isn’t that people like François Bernier and Madison Grant were white but that their theories about race are distasteful. Understanding why they thought as they did—getting a sense of these men and their age, even, yes, empathizing with these folks now considered the bad guys of race ideology—is an effective way to combat racism. You do have to stand in someone’s shoes to see where they’re coming from. And to show where they went wrong. No matter how filthy the shoes.

Such children’s book authors make, in fact, exactly the same mistake made by the Your Skin picture book and countless others: they categorize people by skin. Instead of saying, “wrongheaded intellectuals did this” they start with “white people . . . “ Low on story, big on lecture, these books promote not just racism but a kind of illiteracy—children are told what they’re supposed to believe or to say or not say. But they don’t get what a story gives them: a way of feeling what the characters feel and why. Without that, there’s no hope of fostering empathy. Or ending racism.

It’s the stories—the people in the stories and how they converse and change—that make the changes. In The Secret Garden, two children whom everyone calls “ugly” because they are ugly start out with ugly ideas about race and illness. They grow and develop into healthy, loving beings. That’s the lesson of the book; Mary becomes best friends with the Sowerby family, servants to her Uncle Archibald. It’s pleasant to think how horrified her racist, snobbish mother would have felt—and satisfying to know she can no longer influence her daughter. The love and independence gained by two unhappy children who cast aside their prejudices is the real lesson of the book.

So good! I love the dialogue you include, in which Martha shines. I was enchanted by A Little Princess as a child and loved her nobility in poverty—and the transformation of her attic!

Read this book several times as a child and there have been a few good film adaptations too, a deserved classic.