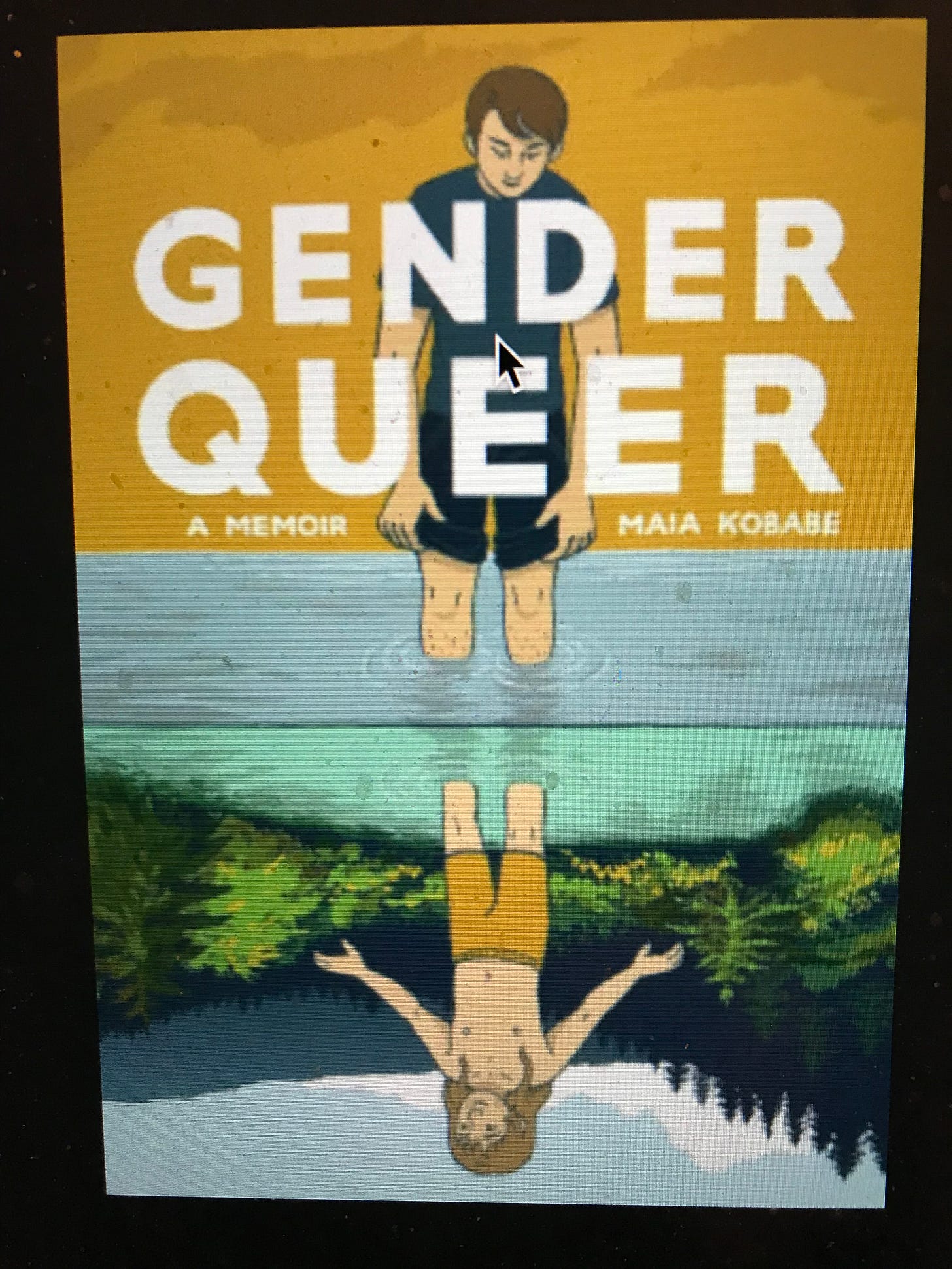

At the top of Republican and conservative lists of banned books are Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer, (2019) a graphic memoir which I’ve taught to university students, and George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue: A Memoir-Manifesto (2020). Here is Senator John Kennedy (Republican, Louisiana) objecting to both on September 12, 2022. In an interview, Maia Kobabe said, “I don’t think [my] book is for children, but I do think it is appropriate for high school and above.”

That’s an important point. I wouldn’t take kids to drag queen story hour because drag queens are adult entertainment—they’re all about adult sexuality, which can confuse and disturb children. How well I remember my then third-grader saying, “Mommy, I don’t want to read about tickling breasts and hairy penises.” His teacher thought foreplay was part of sex education for eight and nine-old-boys, the result being disgust and a couple of tummy aches. I, like other moms, remonstrated and got the usual response: “Oh, we’re professionally trained!” I wasn’t to worry my silly little Mom head. The other teacher, the sensible, older one, asked the kids to write down all their questions, and she’d answer them anonymously. My child is grown, and once in a while we still talk about what an idiot his teacher was.

If only Kobabe had been able to find a book like GenderQueer when she was a teenager, she says, “it would have meant the world to me.” Sweetie, your teachers must not have known what the heck they were doing. Let me find you some films, some books, some poems. Did nobody take you to the 1961 West Side Story or tell you about Anybodys, the character who looks and acts rather like you? She arose from the imaginations of four gay men who, in 1957, were coming to terms with sexualities that couldn’t be expressed in public without facing what’s now known as doxing and cancellation; she’s been called a “tomboy” and a lesbian and a non-girly girl. How about the subtext of the song, “There’s a Place for Us,” ostensibly about the forbidden love of a Puerto Rican girl and a Polish boy? It’s all about gay and other “transgressive” sexualities, and Anybodys is right there, in 1961, making that clear. How about all that fun self-acceptance in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)? How about the genderqueer M. Butterfly (1988), which came out the year before you were born? Nobody mentioned these? Here’s where I (want to) rant about deficiencies in American education (but will stick to my topic).

Books: Did your mom or your kindergarten teacher never read you the Frog and Toad books? Or The Story of Ferdinand? Or Beezus and Ramona? Spoiler alert: these books, which were around in your parents’ generation and before, celebrate gender-nonconforming characters. And for heaven’s sake, did you never come across this Shakespeare sonnet in high school or college? Do take a long look. That’s the one sending older generations of Shakespeare scholars (mostly men, mostly introverted) into tizzies because “of course Shakespeare is not a homosexual! He is just joking!” It’s filled with puns—“acquainted” doesn’t just mean getting-to-know-you. It’s a pun on that four-letter word for the female genitalia, the one rhyming with “runt.” Notice that Nature “pricked thee out for women’s pleasure”—and yes, that word has been in the language since at least the English Renaissance, but check your Oxford English Dictionaries for details. It’s the previous line that’s intriguing: “adding one thing to my purpose nothing.” The term “nothing” also meant the same thing as that word rhyming with “runt.” My point being—the gender ideologues think they invented gender, just as every generation thinks it invented, or at any rate discovered, sex.

Maia Kobabe and George M. Johnson both explore the confused childhoods and unhappy adolescences of those with atypical experiences: the small but significant minority of folks who feel they don’t “fit the boxes” as Johnson puts it, and who belong to—and are breathtakingly preoccupied by—the dizzyingly complicated, ever-growing list of gender identities. The moments in which Kobabe and Johnson luxuriate over the various and fluid notions of their sexualities seem very first-world problems to me.

I see no harm in either book for the interested sixteen-year-old, maybe fifteen-year-old, despite reactions like this from a gay man and an enraged mother, who feel such books introduce inappropriate forms of sexuality to teenagers, or as the mother put it, “I’d kill someone who showed this book to my daughter!” Lady, have faith in your daughter. If she’s gay, you won’t be able to convince her to become straight, and vice versa, just as you couldn’t convince me to like cherry pie, which tastes nasty. Could I convince you to like kimchi if you felt, as several friends tell me, that it smells like excrement?

No, the real danger of these books for teens is their banality: Here’s a sample from All Boys Aren’t Blue: “I used to daydream a lot as a little boy. But in my daydreams, I was always a girl. I would daydream about having long hair and wearing dresses.” He goes on to say that in retrospect this didn’t happen because he believed he was in the wrong body, because he felt he was acting “girly.” And that a girl was the only thing he could be.

Yawn. Why read this pedestrian prose when you can read Shakespeare? Or Walt Whitman? Or Christina Rossetti? Not to mention Emily Dickenson’s poems about Sue? You go look those up.

"The curriculum that is being taught in most school systems is still heavily geared towards the straight, white, male teen," Johnson claims, making a case for his “Black, queer” writing. But if you’re looking for a good way to get across that teenage experience of “must have sex this red-hot instant!” and the potential regrets—disgust prompting a longing for a shower to wash off the experience—you couldn’t do better than Shakespeare’s “Th’Expense of Spirit in a Waste of Shame.” To perceive this poem as a portrait of experience limited to white men is to stretch reality to the breaking point.

Senator Kennedy objected to Johnson’s graphic depiction of anal sex beginning, “I put some lube on and got him on his knees and I began to slide into him from behind.” I find this a porny passage, as do most readers, though one of its defenders felt it should be read as an example of sexual abuse. I think depictions of sexual abuse are only useful when they show how the writer transcended the experience—somehow found the strength to cope and move on where most would be crushed. A good example of such writing is in Maya Angelou’s (unfortunately frequently banned) I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Raped when she was eight years old by her mother’s boyfriend, Angelou manages to bring together two voices: the hurt, shocked voice of her child self, lured by her wish for affection, and her adult judgement of—miraculously, even pity for—the rapist. That’s a book from which a girl with a traumatic history of sexual abuse could benefit: she’d gain courage by seeing how Angelou overcame a terrible, humiliating experience and went on to become a successful dancer, poet and writer.

I would rather see adolescents and young adults reading Shakespeare than Johnson. About Maia Kobabe’s work I am divided. Some of it seems straightforward, but I have the impression much of her story is not being told. Portrayals of her body and of any erotic feeling are almost always filled with anxiety and disgust. There’s one particularly disturbing panel showing her feeling of being impaled after a routine gynecological examination. This suggests two possibilities to me: either she had the somewhat rare (apparently unrecognized) condition of a septate hymen, which can make inserting a tampon agonizing, but which is easily fixed with a routine surgery, or she had some traumatic sexual experience and either does not recall it or doesn’t wish to mention it. Immense trauma after a routine exam, resulting in physical agony and hours sobbing afterward, goes way beyond the typical teen emotions of insulted dignity and embarrassment. Kobabe’s claim of feeling plenty of support from a loving, accepting family seems to me dubious.

Someone posted a Facebook message about bullets, not books, harming children, and that’s mostly true. It won’t damage your child to read All Boys Aren’t Blue or Gender Queer, but it won’t facilitate intellectual or emotional growth either. Current practices deprive teenagers of having their own hunches and making their own discoveries in peace. Unasked for advice is seldom appreciated. Answer the questions of a teenager who asks for help or who looks anguished. Shakespeare is good for teens, because he doesn’t just roll out a sexual experience; he explores its meaning in ways to which anyone who has ever experienced or only dreamed of a sexual experience can relate. He covers the good and the bad, offering a cornucopia of detail. When I was in high school, we giggled over John Donne (you mean people had oral way sex back in the 17th century?) Reading is safer than doing, of course, and the aware teen makes wiser choices after a deep dive into the minds of the poets who seemed able to hear every note of human experience.

My main concern with Johnson’s and Kobabe’s books is their quality: they aren’t particularly well written, and they fail to negotiate the very real space between porn and directness. They impress me as victimology with a dash of scandal. Maia Kobabe claims to have found inspiration in in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, which tells a hidden story: Bechdel’s effeminate and secretly gay father tries to suppress her boyish ways, insisting she wear dresses, which she hates—because he doesn’t want anyone to know how feminine he feels. Like any good memoir, Bechdel exposes with humor and kindness harmful family secrets, secrets destroying intimacy and happiness. I can highly recommend Bechdel to any adolescent; I can’t say the same for Johnson or Kobabe.

None of these books should be banned. I taught Kobabe because I was looking for something about gender identity and at the time, hers was the only book around. My students also wondered about her level of distress, suspecting there must be something she wasn’t telling her readers.

Memoirs have to be completely honest, no matter the cost to writer or family, to be any good. The best began with whatever’s eating the family alive: “You must not tell anyone,” Maxine Hong Kingston writes, remembering what her mother said about Kingston’s aunt, unmentioned and unmentionable until that moment. Raped, impregnated and tormented by the whole village, the aunt drowns herself and her newborn. Kingston’s mother tells the story as a warning when Kingston gets her first period. Helen Fremont discovers her Jewish heritage: parents traumatized by their World War Two refugee experiences raise her to believe she’s Catholic, in a misguided attempt to protect her. Memoirs failing to explore such poisonous secrets—the secrets inspiring family members to react with “she’s misremembering! Delusional!”—are usually not worth their salt. Memoirs are typically nothing without an exposé of the false narratives to which families cling at enormous personal cost. But still—I’d never ban Kobabe or Johnson. I just don’t find much insight in them.

Excellent analysis of these books! "I'd never ban Kobabe or Johnson. I just don't find much insight in them" -- exactly my view, and for the same reasons you note in the main portion of your analysis!

We recently had a challenge to Gender Queer in the library where I work. While it isn't my cup of tea, we also want a diversity of viewpoints in our collections, so it was added to our adult collection (we also want adult patrons who have heard about the controversy surrounding the book to be able to access it and *decide for themselves* what they think of the book!). We were thus able to defend the book from the challenge, which focused on the question of "why are we putting this book out for little kids?": We aren't -- it's in the adult collection, where kids won't just stumble across it. And any parents who want to make sure their kids don't find the book just need to take their kids to the children's department, where they can browse to their delight.

Thanks, Melissa. Next topic?