In the early 2000s when my kids were young, I walked into Books of Wonder in New York’s flatiron district, scooped up basics about pirates and princesses, and gazed with longing at facsimile editions of The Wizard of Oz and Treasure Island.

Wouldn’t want tiny hands tearing those pages or tiny mouths vomiting on the gorgeous covers and besides, those books were out of my price range. How about a classic the kid could hold all by him or herself? One of the Dumpy Books, a series designed as pocket-sized for little hands? How about my childhood favorite, Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo? If I asked for that, would someone get offended? The phrase “politically correct” hadn’t yet died, though it was ridiculed.

Little Black Sambo is one of those stories that took on a life of its own. Helen Bannerman, the Scottish missionary who wrote it in 1899 as a letter to her young daughters, sold the copyright, an act she later deeply regretted. The initial print run of about 21,000 copies was just the beginning. Everyone wanted in on the action, many illustrators reproducing something that would sell—and what sold was often racist stereotypes and caricatures. The book is still being re-written, decade after decade—there’s a version of it set in New England. There’s Julius Lester’s Sam and the Tigers, which is fun, but as he admits, lacks the charm and simplicity of the original.

An African-American clerk smiled, handing the Bannerman original book to me with a nod, a wink and a flourish. I felt as though I’d walked into a speakeasy and spoken the right password. Her conspiratorial look told me yes, it’s okay: this book is a tale of triumph, a yarn championing the fantasy of all small, vulnerable beings: “I am the powerful conqueror of not one but four deadly bad guys—tigers who threatened to eat me up! All by myself I distracted them, handing over my beautiful new coat, trousers, shoes and umbrella, Then, because I was brave, I got everything back, and the tigers melted to butter and I ate them all up in pancakes. I ate more than mommy and daddy, too!” This story radiates the self-confidence craved by small children, who long to be in charge even though they’re not big enough.

But take a crack at almost any website, and you’ll find the term “Sambo” associated with racism, minstrel shows, derogatory depictions of African-Americans. All blackface comedy—even or especially Al Jolson’s—is deemed racist. But like George Gershwin, especially in Porgy and Bess, Jolson’s singing is influenced by his Jewish heritage; both he and Gershwin empathized with similarities between Jewish and African-American suffering. When I watch Jolson’s blackface performance of “Mammy” in The Jazz Singer, I see the kind of painful translation that becomes possible to writers who are skilled in a second language. He is wearing blackface but singing like an orthodox cantor. Not actually in Yiddish, but the sound, the mood, the sorrow—all there. In his autobiographical film, The Jazz Singer, Mary, the woman Jakie loves, says, “There are lots of jazz singers, but you have a tear in your voice.”

Likewise, Oscar Wilde wrote his mystical biblical play, Salomé (1892), in French. Why did the Irishman do this, when he wrote everything else in English? Because this play is a hidden autobiography: the bizarre figure of Herodias and the childish one of Salomé herself were inspired by his mother and his younger sister, who died at age nine. Herod is not too far from his father, who was rumored to have “a bastard in every barn.”

Examples abound. Sabine Reichel’s 1989 book, What Did You Do in the War, Daddy? Growing Up German was written in English, because she found it too painful to write in her native German. I think of Emily Dickenson’s idea: “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant—” which I read as meaning, “tell the truth but in such a way that you don’t quite recognize it—indirectly.”

Jolson and Gershwin displace their loss and pain onto persons technically foreign to their own worlds—but at the same time, whose history is all too familiar. That’s why you have not just Jolson singing “Gus” but Paul Robeson singing “Let My People Go.” African-American singers find solace in identifying with Jewish oppression and vice versa.

But the pain of Jolson is unfortunately understood as “appropriation” instead of what it is--appreciation. Explore most websites about Little Black Sambo, and you’ll typically find adjectives like “offensive” and terms like “whitewashing” and “stereotypes.” Black Mumbo is seen as a mammy stereotype, Black Jumbo as a Zip Coon. Words and images describing race are deprived of context; context is irrelevant, the popular belief goes. Standard practice now dictates that “nigger” is always, in every way, a racial slur, to be experienced as an insult, even or especially in a classroom, when a teacher’s aim is to reveal the past and to explore Mark Twain’s loathing of the institution of slavery, or Countee Cullen’s feelings about having that slur hurled at him when he was a child. Critical thinking evaporates in the hysterical fetishizing of the word.

I’m not buying the censorship approach. Black Mumbo is a loving mother drawn by another loving mother—Helen Bannerman is a folk artist, unskilled but lively, drawing what she sees around her. Bannerman and her husband lived in Madras in the 1890s, the decade in which she wrote Little Black Sambo. Here’s a Madras street scene from that time. Then, as now, the population is mostly Tamil, and her naïve drawings of Little Black Sambo bear a likeness to the people she saw around her, like this Tamil boy. But she wasn’t just relying on observation; she was influenced by—my evidence being a comparison of the illustrations—Dr. Heinrich Hoffmann’s 1845 children’s book, Der Struwwelpeter.

A German psychiatrist, Hoffmann couldn’t find a book he liked for his three-year-old son, so wrote one that is (Wikipedia says) one of the first precursors of comic books, in the sense that it combines visual and verbal narratives. Although every German I know has fond memories of being a small child sitting on Mommy’s lap enjoying the book, anyone coming to it for the first time as an adult notes its gruesome elements: the girl playing with matches burns up; the boy sucking his thumb gets the thumb sliced right off. The German satirist, Jan Böhmermann even produced a video suggesting the book could save Germany’s coddled children. Or at least address the anxieties of their parents.

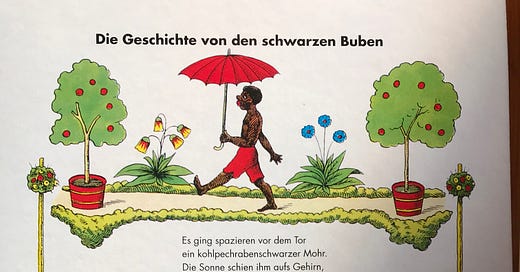

Bannerman doesn’t go for the gruesome, but she loves the illustrations. Here’s one from a poem called, “Die Geschichte von den schwarzen Buben,” translated by Mark Twain as “The Tale of the Young Black Chap”:

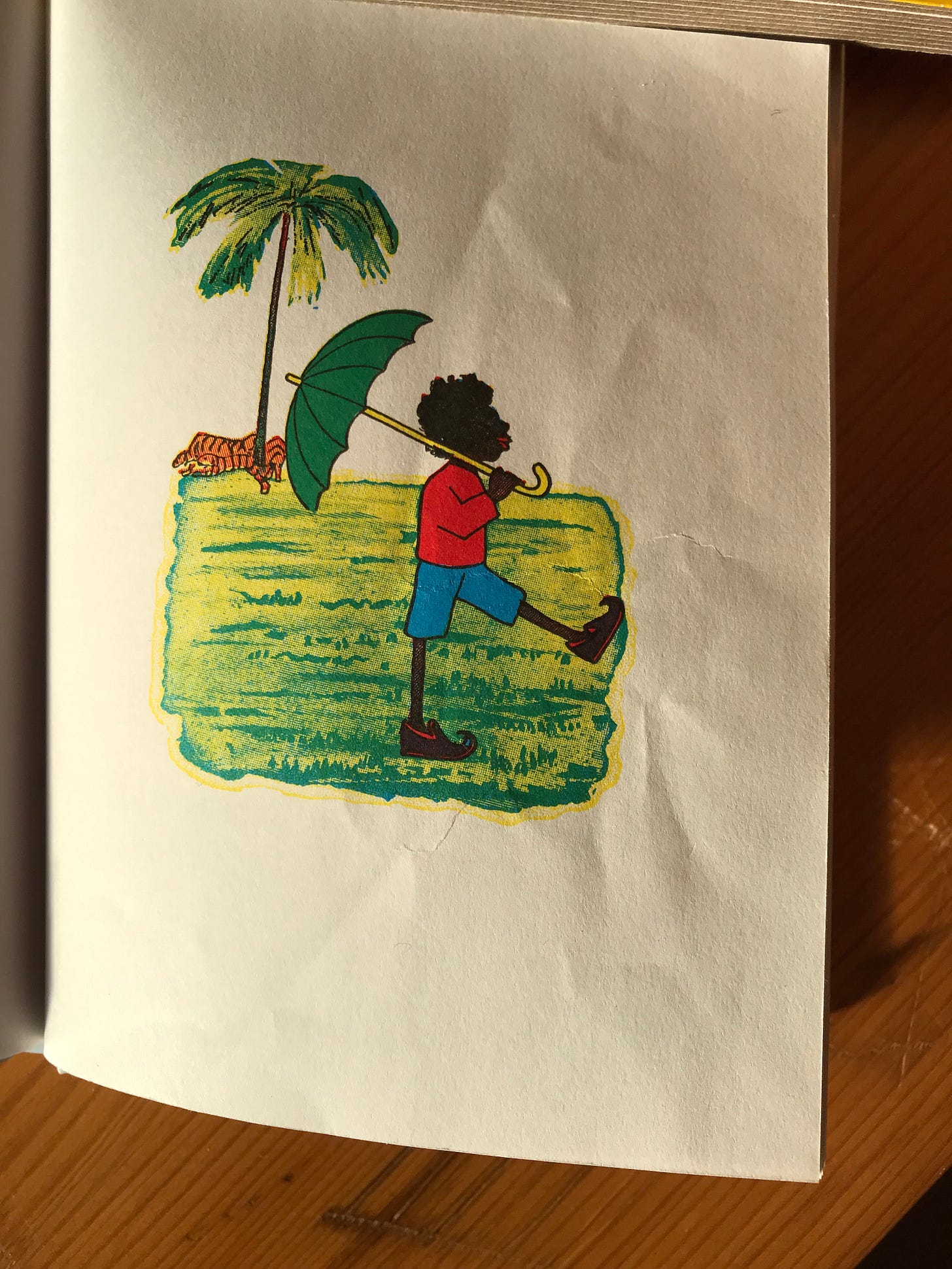

Here’s Bannerman’s illustration of Little Black Sambo with his new umbrella:

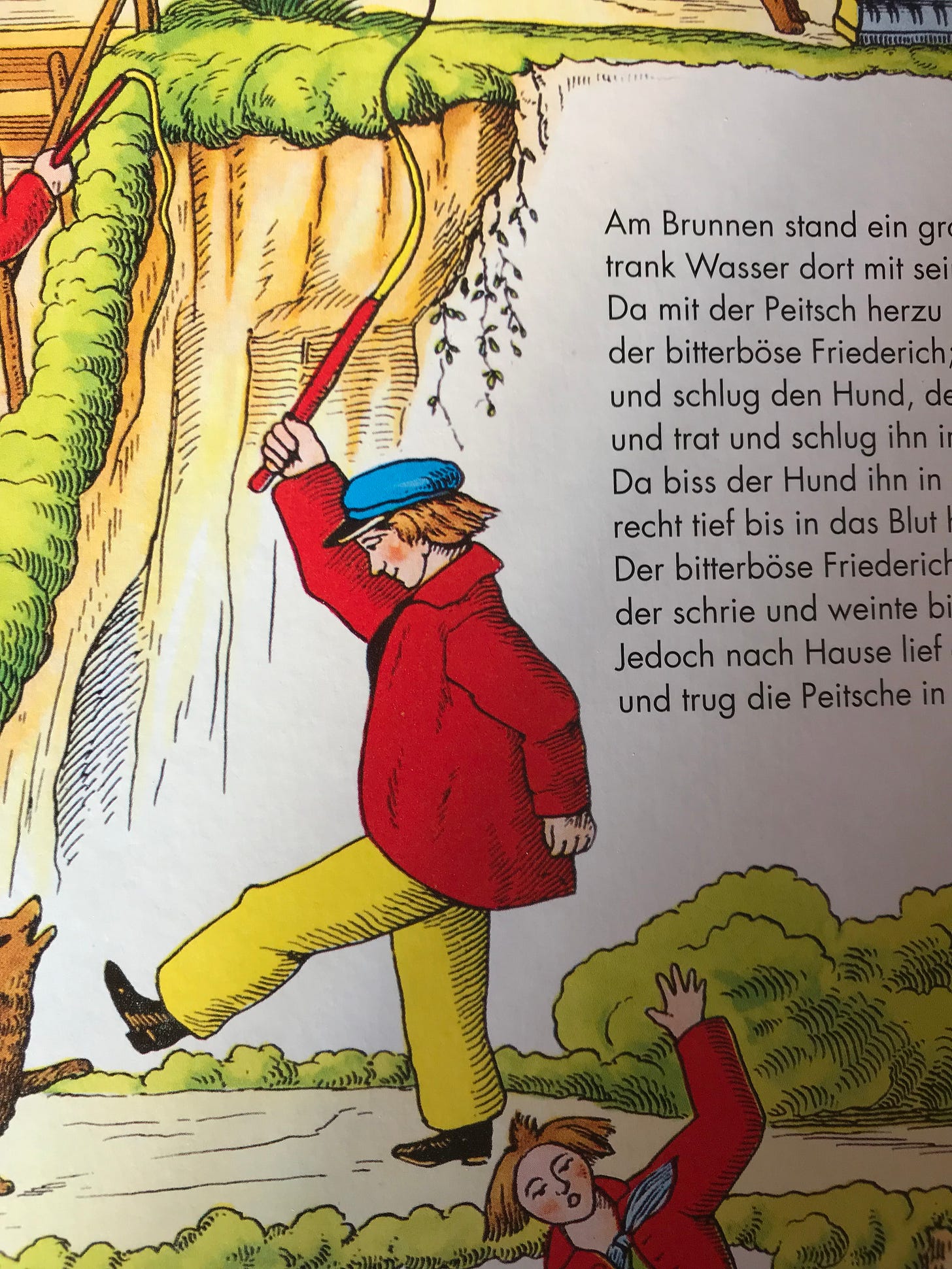

But lest anyone assert that Bannerman or Hoffmann are out to make fun of anything about black people—perhaps the way they walk— note that every Hoffmann figure steps that silly goosestep. Here’s “Ugly Frederick” as Twain translates—though you might also call him “Mean” or “Nasty” Frederick:

Here’s “Hans Stare-in-the-Air,” or the kid who never looks where he’s going:

And here’s the “Terrible Hunter”:

All of this is folk art too, and the white figures are every bit as ridiculous as the one black figure in the book. The point is to ridicule humanity, not race.

But then there’s the name of Bannerman’s hero, which lends controversy to the book, at least in the contemporary mind. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “Sambo” is “of multiple origins,” borrowed partly from French, partly from the Spanish word “zambo,” and possibly from a Hausa name. Although now usually understood as a derogatory term, other meanings included a person of mixed race and a person with bowed legs. The earliest known print use of the term appears in 1657, in Richard Ligon’s discussion of slaves on his plantation in Barbados.

All of which begs the question, was Helen Bannerman using “Sambo” as a racial slur? As an insult? Or just as a descriptive term? I’m betting on the latter. She is filled with admiration for Sambo, and her attitude towards his parents seems friendly. (But, but! I can hear readers spluttering. How could I not see racism in those names, Black Mumbo and Black Jumbo?)

How about those names rhyme? How about they almost rhyme with “Sambo” and that’s the point? Besides, “mumbo-jumbo” is a term denoting gibberish or nonsense

Of course. The story is a fantastic one; if the reader expects realism, then the story makes no sense—it’s gibberish. Children don’t converse with, let alone persuade tigers to refrain from eating them. No real child would think of pointing out that the tiger could carry the umbrella by tying a knot in his tail. The idea that a child could think on his feet as rapidly as Little Black Sambo, or prove eloquent enough to talk the tiger out of eating him is nonsense—and that’s before we get to the tigers running so fast that they melt into “ghi” as the book spells the term—or ghee, as we do. South Asian clarified butter, that is.

Alas, the stain of the name still carries the day, context-free. An American chain of restaurants, Sambo’s, was founded in 1957 by by Sam Battistone Sr. and Newell Bohnett. The name, a combination of their names—“Sam” and “Bo,” suited a pancake house, and various specialties were named after Sambo and his parents. Branding the place with our young superhero’s love of pancakes seemed like a good idea. Right after the death of George Floyd, the restaurant came under violent threat. The name had to be changed. But neither this traditional pancake house nor Helen Bannerman’s illustrations were hateful or discriminatory. The threats to the pancake chain arose from the same lack of critical thinking collapsing Mark Twain’s use of the word “nigger” with that of a nasty bully slinging a racial slur.

It is my cherished hope that critical thinking returns. The illustrations irritated Langston Hughes, riled civil rights activists in the 1930s and 40s, and upset children who were the only black child in their class, especially when the other kids called them “Sambo.” And the many editions and film versions of the story appearing long after Bannerman penned her book really are filled with ugly stereotypes. Then the civil rights movement happened. It bears repeating: we’re not living in the racist 19th century or the racist 1940s.

I’ll take Bannerman’s original any day. It’s always possible to tell a child how people feel about the word “Sambo” now, and how people felt once upon a time. And how Helen Bannerman, sitting on a train heading toward the Hill Station and her beloved daughters, just wanted to tell them a story they’d enjoy. An empowering one, as we’d now say, in which the child wins.

And that’s a feeling energizing anti-racism; a child—a dark-skinned child—triumphs over evil, makes his parents proud and enjoys a delicious dinner, knowing he provided an essential ingredient. His story matters.

But Melinda: does that mean to you that the word should never be used? I think of Lenny Bruce. And I think: when I hear the Euphemism, “n-word” or n with a bunch of asterisks, what’s the first word thst springs to mind?

Well done. Sorting out the wheat from all the chaff.