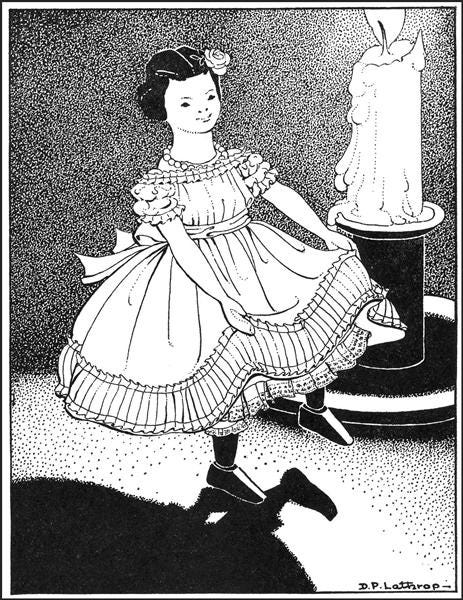

I’d like a “Read Banned Books” sticker just for great girls’ books. Especially those purged from the libraries of elite schools. Like my favorite, Rachel Field’s Hitty: Her First Hundred Years, winner of the 1929 Newbery award. Her name is short for “Mehitabel,” and not for nothing does it mean “God rejoices.” The book details the life and times—from the moment she was first carved—of a wooden doll. No matter what happens, count on a level-headed, if not wry response to any seemingly insurmountable situation. Perched on an antique store’s “very untidy desk,” her back against a pewter inkstand, Hitty writes with a quill instead of one of those “newfangled” fountain pens of which she disapproves:

I must have been made something over a hundred years ago in the State of Maine in the dead of winter. Naturally I remember nothing of this, but I have heard the story told so often by one or another of the Preble family that at times it seems I, also, must have looked on as the Old Peddler carved me out of his piece of mountain-ash wood.

The doll has a typical American past: she is an immigrant, for the old peddler carved her from a treasured piece of wood brought from Ireland. Seemingly destined for a charmed life, certain as she is about mountain ash bringing luck, and “having power against witchcraft and evil,” she survives her many dangerous adventures none the worse for wear, apart from loss or damage to favorite clothing and to her complexion, assaulted as it is by salt water, sun, berry juice, dirt, over many thrilling episodes: Because my clothes had suffered so much from crows, rain, and sharp twigs I was unable to be seen much in polite society, frets Hitty, who need never worry; she continues to be beloved.

I can think of few more enjoyable books to read aloud with your seven-to-ten year old daughter. Dismissing what recent critics have called “problematic,” “archaic,” “potentially offensive,” “inappropriate” and “outdated” language will be a pleasure.

Phoebe Preble, Hitty’s seven-year-old owner, goes raspberry-picking with the “chore boy,” Andy. There’s the first “inappropriate”: back in the day, orphans were often adopted by families who needed an extra hand to feed livestock, milk cows, carry loads—and that’s Andy. He’s a servant, not an equal member of the family. He’s also charged with looking after Phoebe, since he’s a few years older. The two are warned to stay on the turnpike, but the bushes there have all been picked clean. Andy suggests going to the Back Cove, where raspberries are most as big as my two thumbs put together.

Along for the ride in Phoebe’s basket, Hitty overhears the following conversation:

"I heard Abner Hawks telling your ma last night that there's Injuns round again," Andy told Phoebe. "He said they was Passamaquoddies, a whole lot of'em. They've got baskets and things to sell, but he said you couldn't trust 'em round the corner. We'd better watch out in case we see any."

Phoebe shivered.

"I'm scared of Injuns," she said.

Which is just where the collective gasp may be heard:

“It's crucial,” burbles Perplexity AI, “to note that using terms like "injun" or other derogatory language towards Native Americans is inappropriate and offensive, regardless of accent or region. In fact, Maine has a significant Native American population, including the Passamaquoddy tribe, who have a special political status in the state. Respectful language should always be used when referring to Native American peoples and cultures.”

Thank you, preacher. We knew that.

What is the real fear? That your daughter will run around yelling “Injun! Injun!” and behave badly toward Native Americans? How about Native American girls? Would Phoebe’s fears seem outrageous, insulting? Or might they just see her as another little girl like themselves, frightened of what she doesn’t understand? Andy, incidentally, correctly, names the tribe. What Phoebe and Andy see is, in his words, “only some five or six squaws in moccasins, beads, and blankets, who had come after raspberries, too.” It’s Hitty—accidentally left behind by the panicking Phoebe, who watches the women “filling their woven baskets and thought they looked very fat and kind, though rather brown and somewhat untidy as to hair. One them had a papoose slung on her back, and its little bright eyes looked out from under her blanket like a woodchuck peering out of its hole. It was almost sunset when they paddled off through the trees again with their full baskets.”

Is this a negative image? Hardly. The whole scene conveys the relationship between two groups of humans who had reason not to trust each other. Why the censorship? For me, as a child, this was just a story. Had someone said, “dear, we now consider the word injuns to be a bad one, so don’t use it,” I might—contrary kid that I was—have been tempted to say it just to watch the grownups jump. But I already knew the word was old-fashioned, as old-fashioned as Hitty’s clothes, as old-fashioned as Phoebe’s mother not letting Phoebe play with her doll on a Sunday. As old fashioned as hunting whales for fuel. I knew Hitty’s story was one of long ago, but that she still felt the way I felt, only braver. There she was, all on her own, having fallen out of Phoebe’s basket. Next thing you know, a mother crow has grabbed Hitty by the waistband, spiriting her away to a nest in a Pine right above Phoebe Preble’s home!

Poor Hitty—so close, yet so far, spending her days watching the mother crow sling worms into “those yawning caverns,” namely the throats of her demanding children.

As is often the case in tough situations, Hitty takes charge:

"I cannot bear it any longer," I told myself at last. "Better be splintered into kindling wood than endure this for another night . . . I must confess that I have never been more frightened in my life than when I peered down into that vast space below and thought of deliberately hurling myself into it. About this time I also remembered a large gray boulder below the tree trunk where Phoebe and I had often sat. Just for a moment my courage failed me.

"Nothing venture, nothing have," I reminded myself. It was a favorite motto of Captain Preble's and I repeated it several times as I made ready. "After all, it isn't as if I were made of ordinary wood.

Hitty’s stoicism, resourcefulness and affection for Phoebe drive her every decision:

The greatest hardship of all was when I must see Phoebe Preble moving about below me, sitting on the boulder directly beneath my branch so that its very shadow fell on her curls, and yet be unable to make her look up.

"Suppose," I thought sadly, "I have to hang here till my clothes fall into tatters. Suppose they never find me till Phoebe is grown up and too old for dolls."

I know she missed me.

It’s the doll’s loyalty, shrewd powers of observation and common sense that endear her to readers.

As to more so-called “outdated or stereotypical” representations of cultures in the South Pacific and India, I beg to differ. The Prebles set sail on a whaling boat, whaling being the chief source of oil, spermaceti, whale bone and ambergris and an established tradition among some Native Americans, too. And yet—I find in an Amazon reader’s review: “some of the stories, like that of being carried on a whaling vessel, are fascinating, yet at the same time horrifying to those of us who understand whales to be sentient beings.” In most objections, like these, obliviousness to early 19th-century realities overwhelms the reader’s sensibility. Whales, a source of desperately needed goods, were hunted out of necessity. Appreciating them as sentient beings was a luxury, coming only at a time when they were no longer almost the only source for necessary staples.

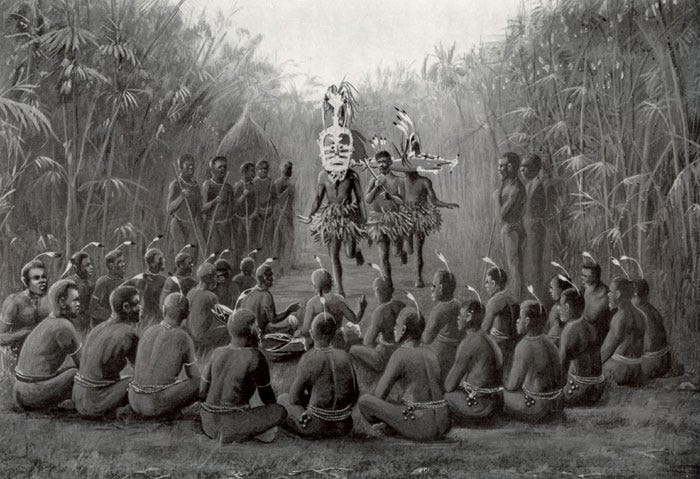

The whale-oil soaked deck of the ship catches fire, and the Prebles manage to flee to an unoccupied South Sea island; it’s unclear exactly where they are, but the local flora include coconuts and hibiscus, and the indigenous peoples, as Phoebe’s father and others describe them, might well be Torres Strait islanders in Micronesia. In 1830—approximately year the Preble family lands among the indigenous people of the South Seas—Phoebe’s father, family and crew must have been among the first Europeans the natives had seen. Christian missionaries arrived about forty years later. Hitty describes the locals as a host of brown men with no clothes to speak of . . . Some carried what looked like crude spears, others had rough shields, and still others spiked clubs. Sounds pretty accurate; here’s some Torres Strait islanders in the 19th century:

Here are some Torres Strait islanders filmed in 1898:

Here are more Torres Strait islanders about nine years ago, welcoming world leaders to the G20 Summit:

Nowadays, descendants of folks like the Prebles pay good money to see unfamiliar cultural traditions, and the tourist industry—which is much more humane than the whaling industry—grows.

But the Preble family weren’t on the island drinking Mai Tais and enjoying the sunsets; they were shipwrecked New Englanders longing for home. Neither the Prebles nor the native peoples had any reason to feel trust. Two entirely different worlds collided, each shocked by the other. As Hitty writes: I have never seen so many bright, black eyes in so many peering faces. I caught sight of nose- rings and earrings under matted hair, of carved necklaces and bands of metal on wrists, arms, and ankles. Of course she hadn’t. Made and raised in Maine, she briefly glimpsed some Passamaquoddy Indians once—the only culture differing from her own. She was used to fully clothed Mainers; the Winter weather and the Christian faith demanded both. Anything different was suspect. The same sort of mistrust influenced the “savages,” who want Hitty because they think she’s a god, and they think controlling the god of one’s enemy means protection from one’s enemy. Not a bad thought. We still think that—only we call it politics instead of religion.

The book’s great turning point comes when Hitty leaves the Prebles forever, falling out of a sleeping Phoebe’s hand. The family has had an exhausting day, and seen many sights—described by Hitty with sadness—including observations frequently tagged as “inappropriate” or culturally insensitive. Like the following:

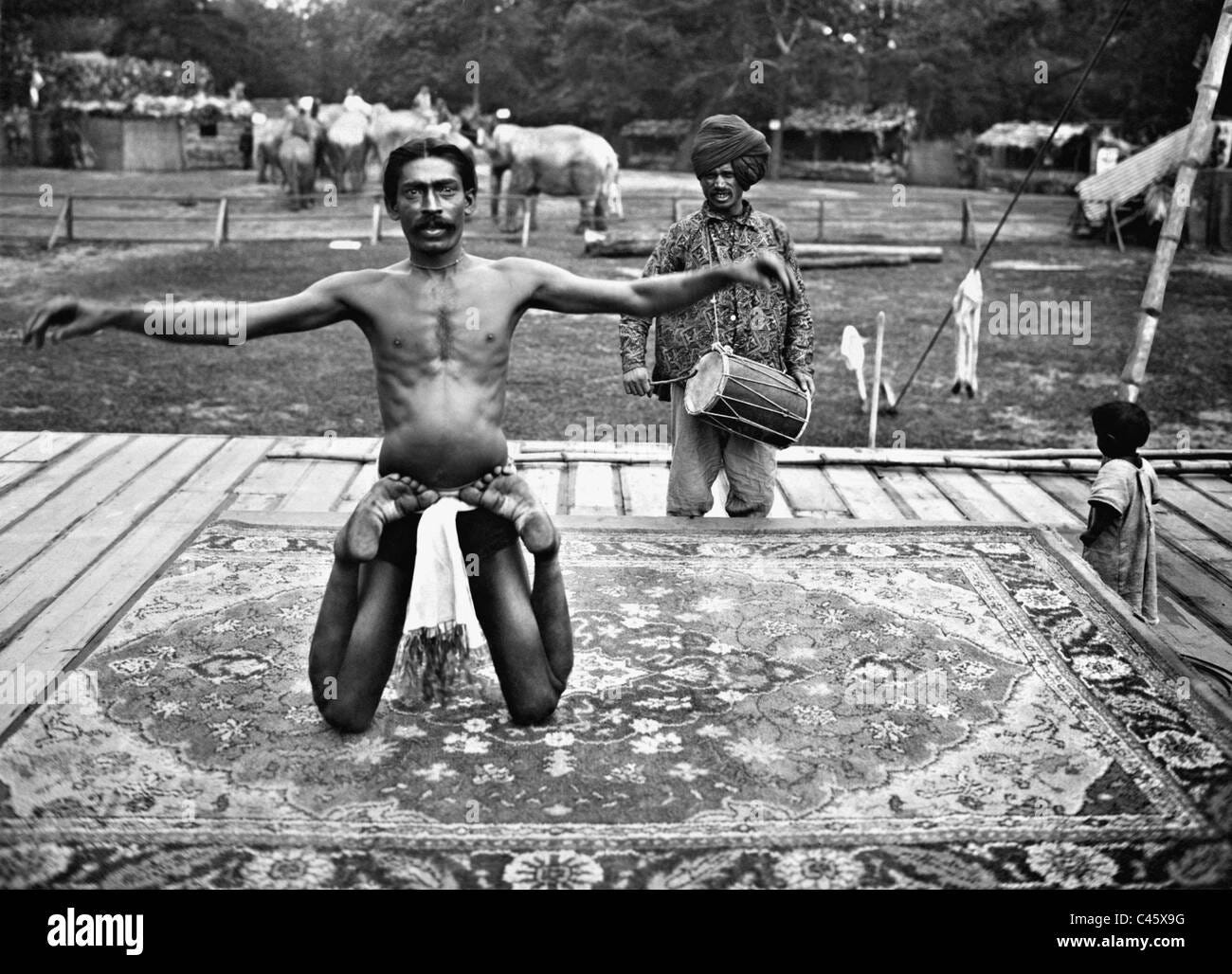

Such a host of little things come back to me as I think of that day--the queer boats, the domes and narrow streets, the whining beggars, and the throngs of robed and turbaned men who walked with a smooth sureness of foot I have never seen in any other place. Sometimes we passed half-naked men with their legs or arms tied up in knots or with their bodies twisted in a manner both grotesque and horrible.

"Fakirs, they call 'em," the captain of the Hesper told us.

"Horrible," gasped Mrs. Preble, as we passed close to one old man who had let his arms grow together in a way that made one shiver. "It's plain indecent, that's what it is. Come right along, Phoebe, and don't look at such sights."

But you can’t object to reality. There really were “fakirs” who twisted their bodies into unusual shapes. Here’s one from the 19th century:

They’re still around Here’s one from our time:

On YouTube, you may find “fakirs” dancing with snakes—the music has changed since Hitty’s day, when the cobra charmer played a small flutelike instrument, but the snakes are the same.

When Hitty falls out of Phoebe’s hand in Bombay (now Mumbai), she ends up with a snake charmer; missionaries purchase her for their daughter, and it is then that Hitty’s adventures become even more geographically variable. She’s in Philadelphia to hear Adelina Patti; she gets to meet Charles Dickens; she finds her way to New Orleans where she’s on display at an exhibition; she’s stolen by a lonely little girl and ends up in the hands of a child on a plantation who calls her “ma chile.” And who is referred to as a “Negro” child. I remember when “Negro” wasn’t a bad word. Through the nineteen fifties and at least until 1967 it was just the polite term for a person of color.

In the end, what’s “problematic” or “archaic” seems to be reality and history that those who would suppress the book don’t want to be known. In 1999, Rosemary Wells and Susan Jeffers adapted Field's took out what they didn’t like—mainly the passages I’ve highlighted here—and arranged for Hitty to meet Abraham Lincoln instead of Charles Dickens. What, because kids today haven’t heard of Dickens? That, sadly, may be true. Read them Oliver Twist! Or Pickwick Papers! Move on to David Copperfield. But that’s another story. I hope I’ve made the case for keeping Hitty’s real language, real observations, real honest thoughts. Assume your child will absorb the doll’s realism and loyalty, and wait for questions before launching into what you, the adult, may find “inappropriate” or strange. Do know this: the doll inspiring Hitty is in a museum in Stockbridge, MA, and the writer who created her has the same lively appreciation for life: