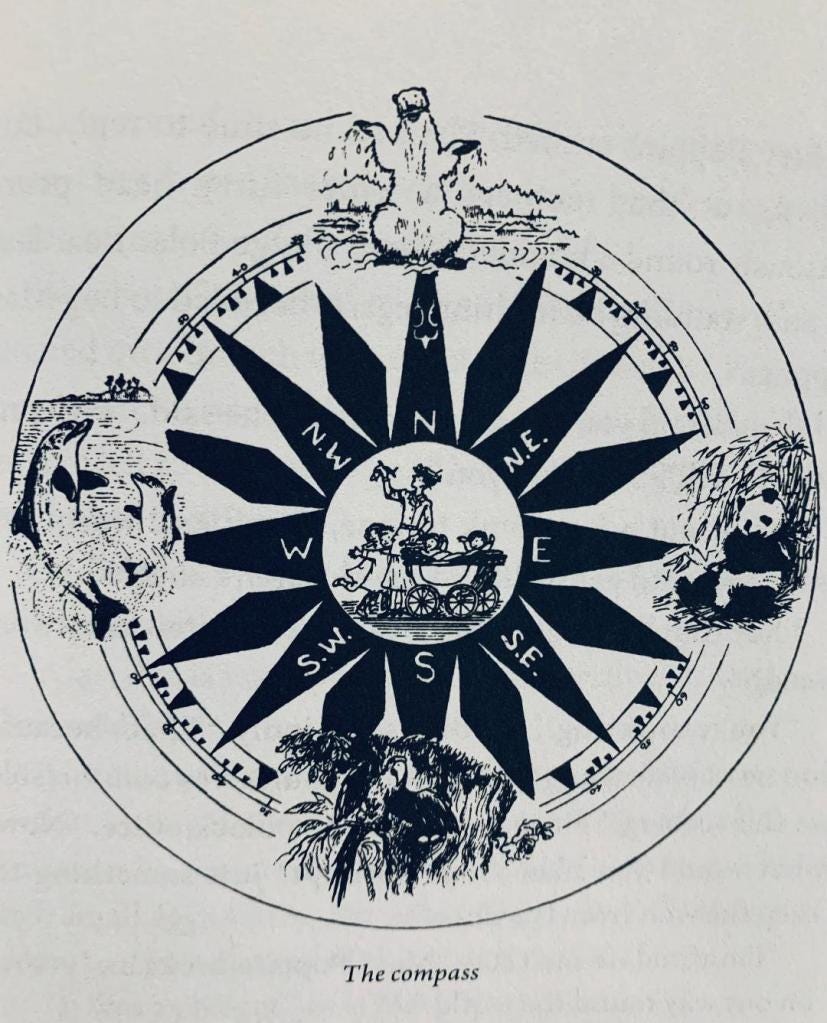

How did we get from this compass—the original—to the polar bear, the macaw, the panda and the dolphins?

The party line: the first compass is filled with “offensive” ethnic stereotypes—not the case, as I will explain—and in the second we’re safe, because you can say anything about animals and nobody will call you a racist (but beware! They might call you a speiciesist). As Lina Slavova observes on her fabulous blog, The Mary Poppins Effect, the original “Bad Tuesday” . . . was a story about the variety of human life on this planet and the possibility for all human beings, despite their socio-cultural differences, to be friends. It was a lesson in openness and willingness to take part in other people’s customs.” Which is lost with the substitution of animals.

In the original version of P.L. Travers’ Mary Poppins (1934) and in subsequent editions through 1966, the first illustration graced the “Bad Tuesday” chapter, in which Michael wakes up feeling naughty, kicks the cook, says he’s glad because her legs are too fat, and spends his day behaving rudely. On their afternoon walk, he dawdles, “dragging the sides of his shoes against the pavement in order to scratch the leather.” Spying something shiny on the path ahead, Mary Poppins asks him to bring it to her, which he does, grumpily. And what is it? A compass—for “going around the world” says Mary Poppins. In the 1934 edition, when Mary Poppins barks “North!” at the compass. The letters slide around, “dancing giddily,” and the Banks children find themselves being greeted by “an Eskimo man . . . his round, brown face surmounted by a bonnet of white fur,” who rubs noses with Mary Poppins. Guess what? Despite the stern warning on Wikipedia that the article needs additional citations for verification, the kiss is a real thing, although the technique differs slightly from the one depicted by Travers. Real Eskimos (that’s not a dirty word, by the way) plant the nose on either side of the recipients nose a few times. They call this kind of kiss a “kunik.” Second, Eskimo (or Inuit) people have brown skin and their traditional fur clothing consisted of caribou, seals and seabirds. Travers’ Eskimo wife offers whale blubber soup—okay, minor inaccuracy: “Muktuk” is a traditional dish made of whale blubber and whale skin, not typically eaten as a soup.

But how many times does a reasonable person have to point out that inaccuracy is neither an insult nor a stereotype?

Before the children get too cold, Mary Poppins explains that they can’t stay because they’re going around the world, and says, “South!” to her compass. And we get to the part the devotees of Kendi and diAngelo love to call racist. The travelers land beside a grove of palm trees with gold and silver sands “as hot as fire” beneath their feet. They are greeted by a man and a woman, “quite black all over and with very few clothes” but lots of beads, and on the woman’s knee is “a tiny black picanniny with nothing on at all” who smiles at the Banks children “as its Mother spoke.”

For starters: in plenty of locations in Africa, (among them Namibia, Tanzania and Ethiopia) people go naked or near-naked because it is the custom to do so. Google these folks to whom Mary Poppins introduces the kids. The man and woman in the grass skirts and beads aren’t “stereotypes”—they are real. There’s a chance Travers was thinking of aboriginal people since she grew up in Australia. The censors are denying rich cultural practices, as many a website describing these tribes could attest.

That word, piccaninny, was typically a derogatory term for a black child in the American South, but we’re not in the American South here. We’re where the word retains its original meaning, namely small child.

The black couple’s speech and behavior is also deemed a stereotype: “Ah bin ‘specting you a long time, Mar’ Poppins,” says the woman, referred to as a negro lady, an entirely polite designation in 1934. “You bring dem chillun dere into ma li’l house for a slice of water-melon, right now. My, bout dem’s very white babies You wan’ use a li’l bit black boot polish on dem. Come ‘long now. You’se mighty welcome.” And she laughs.

Okay, she dresses like certain African tribes or like some aboriginal people but sounds like the deep South (I have relatives—they happen to be white—who speak the way she does). But don’t take my word for it. Dialects change. Technically, the “negro lady” is speaking a version of Gullah, But you never know. When my firstborn was six months old, we lived in a small city in Bavaria. I used to push him in his stroller through an area filled with farmland and a goat pen. One afternoon, a woman who looked to be in her eighties, wearing a dirndl and blond braids curled into buns above her ears gestured toward my son and asked, “Ist ein Bubelah?” Her intonation, her pronunciation, were the same as every Jewish grandma I ever met.

I am from New York City and just knew this lady couldn’t be Jewish—was almost certainly Catholic, given where we lived. My husband explained she was old enough to have lived when Jewish residents populated the area; her dialect and theirs borrowed from each other.

You may think the watermelon is a cliché or a deep South thing, but watermelons actually originated in Africa. The folksy joke about shoe polish is just that—her cute way of recognizing how different these English kids look from her child. She likes them enough to want them to look like her own.

The compass spins again. “East!” Mary Poppins commands. The travelers find themselves “in a street lined with curiously shaped and very small houses shaded by almond and plum trees and people on the street are wearing “strange flowery garments.” Jane tells Michael, “I believe we’re in China,” but those houses are made of paper and an old man who greets them is wearing a kimono—so I believe we’re in Japan, or at least in the idea of Japan. But with a dash of China, since the old man bows low, greeting Mary Poppins. “Honourable Mary of the House of Poppins,” he says as she bows so low that “the daisies in her hat were brushing the earth.” The children don’t realize that they’re expected to bow until Mary Poppins hisses, “Where are your manners?” The old man is identified as a mandarin, and Mary Poppins’ answers are all in the same polite vein. Though his words seem to have been regarded as stereotypical, he’s actually just devoted to Confucian traditions of politeness and bowing. “Deign to shine upon my unworthy abode the light of your virtuous countenance,” he says. Her reply mirrors this tradition of humbling oneself before an honored companion: “Gracious sir,” she says, “it is with deep regret that we, the humblest of your acquaintances, must refuse your expansive and more-than-royal invitation.” All this is merely polite Confucianism.

Another spin of the compass and Mary Poppins says, “West!” The setting is now deep pine woods, and a Chief Sun-at-Noonday in doeskin. He’s overjoyed to see his guests: “Morning-Star-Mary!” he says, touching her forehead with his. He offers the children a supper of fried reindeer, but Mary Poppins indicates they’ve got to head home. Glancing at Michael, the chief suggests they stay long enough for “this young person”—Michael—to “try his strength” against the chief’s great-great-grandson, Fleet-as-the-Wind. Michael races against the boy but can’t keep up, and Mary Poppins gets them home so that he finds himself racing in the park near Cherry Tree lane. Michael’s bad mood has not improved—Jane is crowing about the wonderful box that takes you around the world, but Michael thinks it belongs to him. He manages to snatch it off the dresser and shout, “North, South, East, West!” only to find the figures of the Eskimo, Indian, Chinese Man and black man coming toward him angrily with weapons. Terrified, he screams for Mary Poppins, who come with hot milk and soothes him, silently disappearing the people. Michael suddenly feels good and wants to give everyone a birthday present. He drinks the hot milk and feels much better.

P.L Travers had spent time among either Navaho or Pueblo indians and frequently wore their jewelry. The portrait of Indians here is part myth and part memory. Travers had been given an Indian name and told to keep it secret. The chief in this episode knows Mary Poppins’ Indian name and she knows his; as in each of the other episodes, they address each other as equals.

My heart leapt up when I found P.L. Travers’ Mary Poppins, complete with Mary Shepard illustrations on the shelves of my former school’s library.

Leapt up too soon: the school has the 1997 edition, the one you’ll find on Amazon. Unless you specifically request the 1934 original, or an edition published in the early 1960s—before the censorship. Take a wild guess what the 1934 edition now costs. On ebay, prices range from $4,229.71 to $75. (plus shipping). Pre-censorship editions from the early sixties are slightly less, but still expensive.

In 1967, what Wikipedia terms “offensive words and stereotypical descriptions and dialogue” were removed from the “Bad Tuesday” chapter. In 1980, after the San Francisco Public Library system banned the book, citing “negative stereotyping,” P.L. Travers reluctantly agreed (libraries and publisher twisting her arm) to revise the story—so all the very charming people gracing the pre-1967 editions have disappeared and instead we have a polar bear (bye-bye, Eskimo family), a Hyacinth Macaw (no more African couple!), a Panda (so long, Chinese man!) and a Dolphin (who is so much less interesting than Chief Sun-at-Noonday, the Indian, and his great-great-great grandson, Fleet-as-the-Wind.)

In 1982, Travers expressed regret over editing the books, stating: "What I find strange is that, while my critics claim to have children's best interests in mind, children themselves have never objected to the book. In fact, they love it."

If you don’t have access to any edition, there’s a fabulous side-by-side comparison of the various versions here.

The entire message of the original edition is anti-racist; Jane and Michael see lands and peoples they’d never have the opportunity to meet without Mary Poppins’ magic, and they learn how to behave toward these people—politely, and in style of their cultures.

That, obviously, is the message lost with the substitution. Always relatively “safe” to talk about animals, and nobody will tell you you’ve got this or that detail wrong.

What a loss—for literature and for children. I think of Porgy and Bess. What if some fool wokester decided a White Jewish guy couldn’t or shouldn’t write in a dialect spoken by Southerners? Oh, my. Let’s hope the wokerati keep their mitts off of Gershwin. The thought of “It ain’t necessarily so” re-written as “It is not necessarily the case!” gives me a tummy ache.

This is wonderful! You are doing important work in resuscitating and rehabilitating the original versions of children's classics. Keep it up!