Read enough mom blogs, and you realize the terms “racist” and “stereotype” now mean the same thing, namely, “any representation of a nonwhite person.” That’s the denotation; the connotation is “be afraid. You might be accused of cultural insensitivity.” You might be called “racist”—a word more dreaded than the hyper-fetishized n-word. You might be fried on TikTok. Fantasy is out—any inaccurate or old-fashioned detail could cancel you. (For instance, is The Three Bears transphobic or homophobic because it presents a nuclear cisgender family? Is Sleeping Beauty bad because it shows a prince kissing an unconscious woman who cannot give consent? “Romanticized sexual violence” is what one site calls the romantic kiss. Not to mention the defloration image, with that spindle thingy. Hansel and Gretel demonizes older women? And so on.)

This flattening of “racist” and “stereotype” into one meaning is particularly noticeable in commentary on three award-winning tales derived from Asian sources:

•Arlene Mosel’s Tikki Tikki Tembo (1968), illustrated by Blair Lent.

•Claire Huchet Bishop’s and Kurt Wiese’s The Five Chinese Brothers (1938), illustrated by Kurt Wiese.

•Marjorie Flack’s and Kurt Wiese’s The Story About Ping (1933), illustrated by Kurt Wiese.

Tikki Tikki Tembo takes up the traditional Chinese elevation of the firstborn male, something that also occurs in Japanese, Jewish, and other cultures. The story is essentially a myth explaining why the Chinese have short names—which they don’t, necessarily. Nor does any Chinese person have a name sounding remotely like that of the firstborn son, which begins with “Tikki Tikki Tembo” and rolls on for another fifteen syllables. The real point is to repeat that long, melodic name in a musical way.

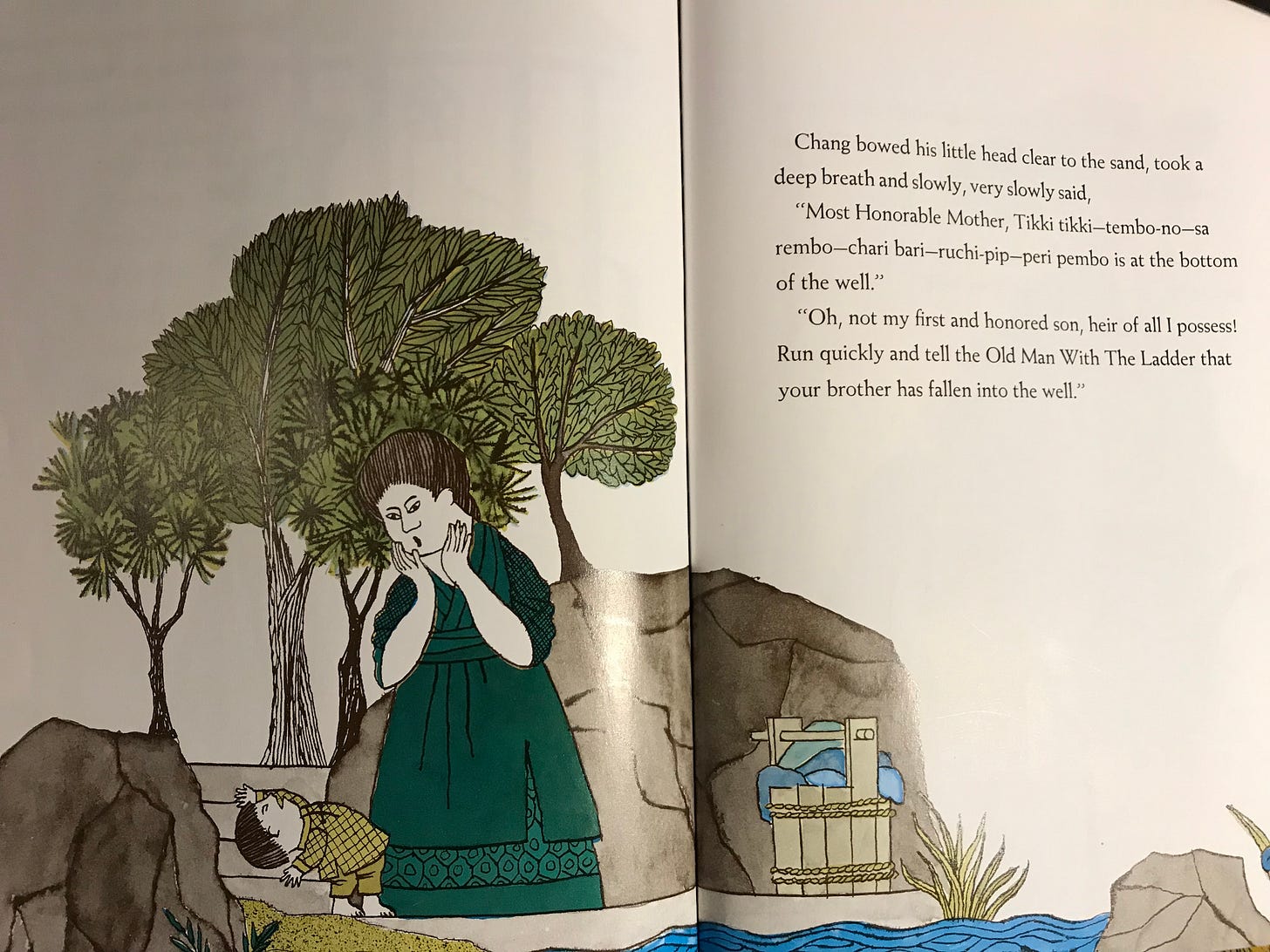

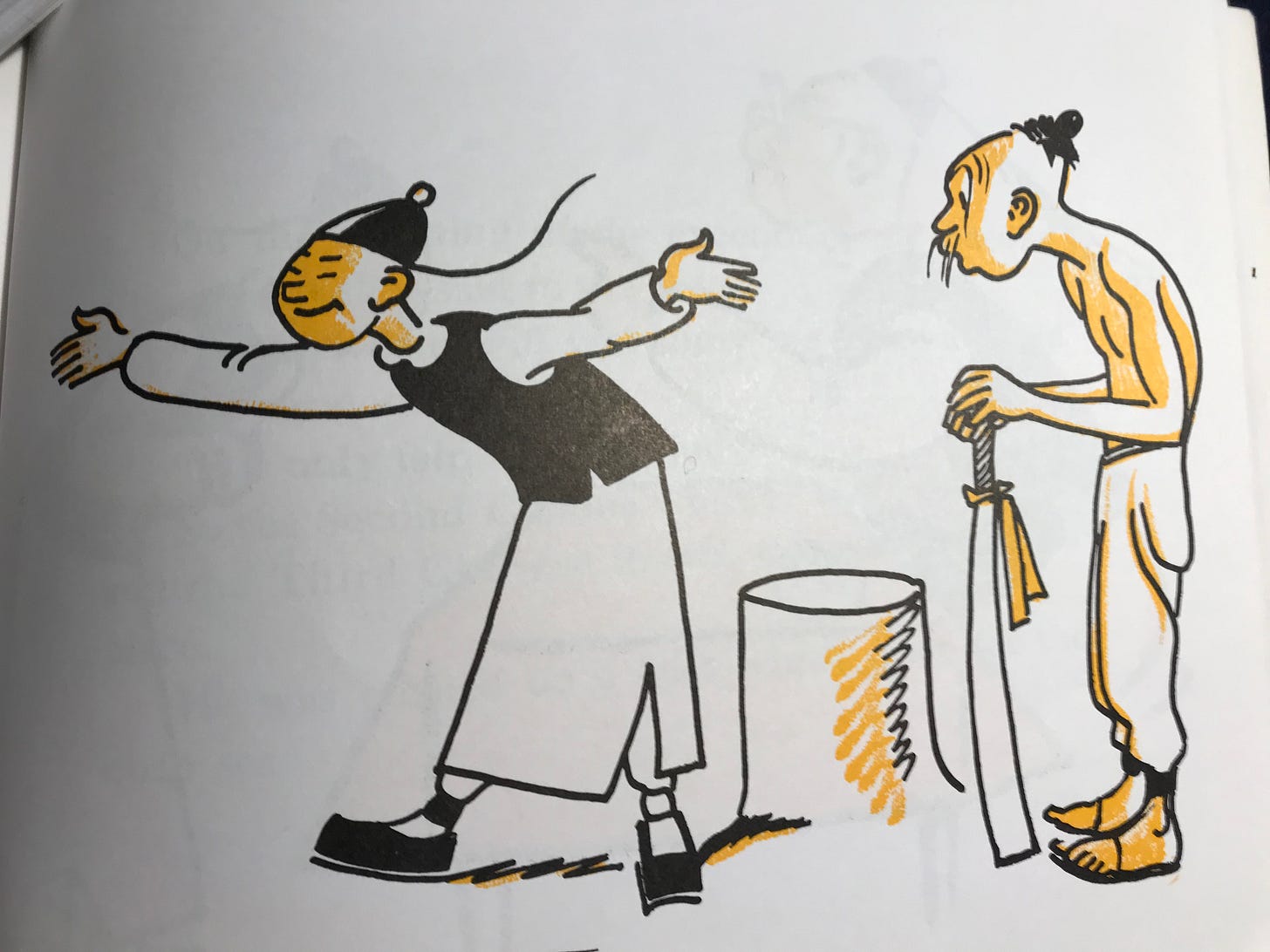

Nothing about the actual story is likely, as any child might figure out: the mom favors the eldest blatantly, giving him the multi-syllabic name supposedly meaning “the most wonderful thing in the whole wide world,” while the youngest is called “Chang,” meaning “little or nothing.” The boys are told to stay away from the well, but since no mom is helicoptering around, they fall in, one by one. Chang falls first, and his brother goes to the mom, who tells him to get the old man with the ladder, who rescues the kid. But when Chang’s brother—he of the twenty-one syllable name—falls in, the mom spends so much time making Chang properly pronounce each syllable that the brother almost drowns.

But they all live happily ever after anyway. If your school-age child imagines any of this tale is true, then hey, kid, there’s this great bridge in Brooklyn—and it’s for sale!

When I read critiques accusing the authors of banal cultural stereotyping, I wonder whether the complainers ever read Little Red Riding Hood. Would anyone conceptualize that as a series of stereotypes about naïve little girls or negative depictions of an endangered species, namely wolves? (But see this parody). And I think of this song, Sam the Sham’s version of the story. Some might deem it sexist or pedophilic. But it’s just fun, the way these classics based on Chinese and Japanese culture are just great. They’re fairy tales—remember those? The Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen stand accused of sexism and other crimes—by “presentist” academics. Would an actual reader call Jack and the Beanstalk a misrepresentation of _________________ (fill in the culture of your choice). No, because we know it’s just a story.

Then there’s the matter of eyes. I can’t begin to tell you how much agonizing goes on over whether it’s racist to draw an Asian eye as slanted, but Asian writers of children’s books seem less likely to worry about this. Taro Gomi’s hilarious Everyone Poops was first published in Japan in 1977 and translated into English. Every figure—not just humans—has slanted eyes, including the elephant. The book is the hands-down favorite of moms trying to toilet-train toddlers. The skin tone of the humans in the book is, incidentally, orange. Which is not exactly representative of most Japanese skin.

Likewise, The Five Chinese Brothers has been accused of racial stereotyping because the Chinese figures have yellowish or orange skin in the pictures. Which, as I’ve detailed here, has more to do with the costs of printing before the internet than it does with reinforcing any stereotype. The story concerns a man who is blamed for the accidental drowning of a young boy and sentenced to death. The drowning’s not his fault: he swallows the sea so a young boy can find unusual fish and stones and algae on the understanding that the kid will return when called—which he does not. Eventually the young man can’t hold in the sea and it erupts from his mouth, drowning the boy. Luckily, he has four identical brothers who each have a secret power—one has an iron neck, so when they try to behead him, he stands up, smiles and walks home.

After four brothers have escaped execution, the judge (having no idea he’s seen four out of five brothers) decides the first one must be innocent. The artist, Kurt Wiese, lived in China as a young man from 1909-1915 and like the author, loved the country and saw his illustrations as a token of admiration.

The Story About Ping concerns a “beautiful young duck” on the Yangtze River living in a boat with his “mother and his father and two sisters and three brothers and eleven aunts and seven uncles and forty-two cousins.” I loved that part as a kid. The ducks are let out every day to hunt for snails and little fish. Ping always tries to get back the moment he hears the Master of the boat cry “La-la-la-la-lei!” because the last duck in gets a spank on the back. But one day, Ping doesn’t hear the call until he’d be last, so he hides. Chasing after some rice cakes in the water, he’s captured by a little boy and narrowly escapes becoming dinner.

After this, he swims back to his boat and even though he’s last, takes the spank so he can be back with all those relatives. As usual, some complain about the yellow and orange shades of skin and the shape of the eyes, and wonder about the “large birds” Ping sees who hunt for fish with a tight ring around their necks—there are those who consider this some cruel invention, but like everything else in the book, it’s real. The boats look like real Chinese boats, the people like those whom Kurt Wiese saw when he was living in China.

All three stories treat Chinese themes, although Tikki Tikki Tembo has been criticized for blending Chinese and Japanese elements, or for mistaking a Japanese tale for a Chinese one. And it’s been accused of racism and “cultural sterotyping”. But not by all Chinese mothers, some of whom love it.

The mom blogs say Tikki Tikki Tembo was written when it was acceptable, in 1968, to make fun of Asians. That’s now how I remember 1968. The author and illustrator are no longer around to defend themselves, but Arlene Mosel said the story was one she’d heard in childhood; she may have mixed up Chinese and Japanese culture, but while many a mom blog interprets this mistake as a sign of thinking Asian people “are all alike,” there’s just as much justification for pointing out the influence of Chinese culture on the Japanese. About which you may read in more places than Wikipedia. But maybe Arlene Mosel is guilty of a difficulty in distinguishing the Chinese from Asians of other ethnicities?

The Western difficulty in telling apart Asian ethnicities shouldn’t be seen as white supremacist bigotry; anyone seeing an unfamiliar ethnicity for the very first time may have difficulties telling people apart. I can hear the chorus of social justice warriors shouting, “But Tikki tikki tembo-no a rembo-chari bari ruchi-pip peri pembo isn’t a real Chinese name! What if your child thinks it is?” Well, then, Mom, you do what you do when the kid asks where rainbows come from or what a hemorrhoid is. You explain. If the kid’s toddler age and nodding along with the recitation of the funny name, you might point out that by the way this isn’t a real Chinese name, but you needn’t imagine the worst: your children will not end up thinking mean, inaccurate things about Chinese or Japanese people because you read them this story. Maybe the real question is, “What if my kid shouts that long, non-Chinese name in the supermarket and someone hears him and thinks I’m a racist?” Tell them you’re not. But I recall listening to Tom Lehrer’s “National Brotherhood Week” in the car with my husband and then two-year-old, and realizing it wasn’t cool for the kid to belt out, “and everybody hates the Jews!” especially since we were living in Germany. So, yeah, we censored that one until the kid was old enough to understand satire.

I was amused to find the conservative commentator Dinesh D’Souza, born and raised in Mumbai and ethnically Indian, confessing to an inability to tell apart two white girls when he was an exchange student in an American high school. That reminded me of my childhood response to the population of New York’s Chinatown. My father took me there when I was seven, and I vividly remember thinking: everybody has straight black hair and black eyes! How do they tell each other apart? That didn’t mean I was a budding racist. It meant I was used to registering red hair, blonde hair, brown hair, curly hair and straight hair. It meant I was used to telling green eyes from blue eyes and brown eyes. It meant I could tell white skin from black, but hadn’t encountered Asian, except for one friend who was half Chinese and half French-

Canadian. It meant I hadn’t yet seen features that to me were subtler, like the shape of a person’s cheekbones, eyebrows, face and nose, or someone’s characteristic expressions, or all the ways in which people tell apart persons from their own ethnicity. As I grew, I learned, gradually, to see the differences. Would I have learned if someone had shamed me for thinking, on first encounter, that all Chinese people. looked alike? Fear would have stunted my ability to perceive and learn.

While I’m on a roll, I confess to experiencing difficulties in telling Scandinavians apart. All their languages sound like Swedish to me. Those Nordic types—they all seem so tall! Sometimes I even think somebody from the Netherlands is Swedish or Danish or Norwegian. Would you call this difficulty “racist?” Would you see me as insensitive because I have trouble remembering the name of the airport in Reykjavik? Which is Keflavik. Or might you just say, “Ok, Boomer,” and admit that Scandinavian countries have all their own traditions, but influence each other? Just as numerous Asian countries have all their own traditions, but tend to cook with ginger and garlic? Scandinavians and Dutch people might be lumped under “they all eat herring.” Many do. Racist culturally insensitive stereotyping to say so? Bah, humbug.

yeah, you're racist, and making terrible excuses for being racist. It's a shame you've lived this long and still haven't learned anything about how the world works. You're going to "fuse" all of eastern asia together? And the audacity to just forget or dismiss thousands of years of differences, conflicts, and cultural divergence is incredible on your part. Do you realize that there's over 2 billion people there? The entire fucking population of Caucasians is about a third of that. It'd be like saying every white person, anywhere in the world looks the same and shares the same culture. Utter nonsense! The fact you use Scandinavians as an example of "See, I also think white people look the same" is just insulting. There are less than 30 million people of Nordic descent in the entire world. That is 1.5% of the population of asians you're fusing together. So mathematically, you're racial insensitivity towards asians is 67 times larger than the racial sensitivity towards those of a Nordic background. I don't know, when you're 67 times more racist towards one group of people than another, I feel that's pretty fucking racist. And the story of not being able to distinguish people as a child, great, that happens to all of us. But the expectation is that you GROW and MATURE like everyone else. Or are you telling me you that you stopped developing at 7? I guess that could be an excuse for this garbage you're spewing. Perhaps the worst thing about is that you think it's OK to excuse or overlook the racism that affects someone else. It ain't about you honey. Just because you don't think it's racist doesn't mean the billions of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean people should be ok with this awful, ignorant, made up mish-mash of their histories, languages and cultures.

Oh and people who cook with garlic and ginger must have some sort of connection? Get the fuck out of here with that! EVERY good chef uses garlic and ginger when the recipe calls for it. Tell me you eat shitty, bland food without actually telling me you eat shitty, bland food why don't you.